Working with veterans is one of the most rewarding aspects of my job here at the Museum of Aviation. The stories and experiences of these men and women are always interesting and often heart-wrenching. I grew up hearing these types of stories from my father. His experiences with life and war were very real to me and gave me a great appreciation for oral history from an early age. There is simply nothing like hearing a person’s story in his own words. The light in their eyes and the tone of their voice tell so much more than words on a page ever could. Even so, after hearing so many of these unique stories it is easy for historians to become somewhat jaded to just how powerful they are. This type of complacency is something that historians try to avoid but can still affect us.

Last week I had the opportunity, along with our curator Mike Rowland, to visit with Arthur Rohr. During World War II, Mr. Rohr had an extraordinary experience.Rohr’s B-25C was flying a night mission over Sicily on July 16, 1943 when the left engine exploded. Rohr was in his position in the top gun turret and witnessed the cowling peel from the engine and flames starting to lick the side of the airframe. Rohr made his exit from the B-25 in a non-traditional manner; the exit panel in the floor at the rear of the aircraft was stuck and Rohr jumped on it with both feet to get it unstuck. When the panel came loose, Rohr fell through the open hatch and was knocked unconscious when he hit his head on some part of the aircraft.

Arthur Rohr stands next to the B-25J at the Museum of Aviation. He is pointing to area where the hatch would have been located on the B-25C that he jumped out of over Sicily.

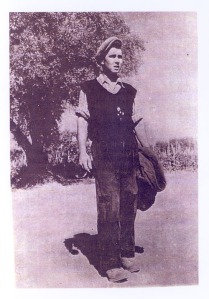

Rohr awoke the next morning with a large gash on his head, miles behind German lines. An interesting note on this part of his story, the parachute that Rohr was wearing had to be opened manually. Yet, Rohr has no memory of opening the parachute before he was knocked unconscious. Rohr says that the Lord was looking out for him that night over Sicily, and attributes his parachute opening to that. There are far too many details of Rohr’s story to include here, but over the next 15 days it was a fight for Rohr to stay alive and free. He avoided German patrols, begged for food from local citizens, traded his uniform for civilian clothes and eventually made his way back to his unit.

Arthur Rohr in the civilian clothes he wore while behind German lines in Sicily. These are the same clothes that he donated to the Museum of Aviation.

Mr. Rohr went on to work for North American Aviation, the company that built B-25’s, after World War II. He came to Georgia when he took a job with Lockheed and still calls Marietta, GA home. Rohr visited the museum last week to donate the civilian clothes he wore while evading capture in Sicily. He has kept them through the years, and although they have deteriorated some, for the most part they look as they did when he last wore them many years ago. As I sat with Rohr and listened to his story, two things impressed me. The first was Rohr’s clarity in remembering events from so long ago. The second was his sincerity in making such a donation. It struck me, as I sat listening, what a powerful and moving sentiment such a donation is. Here sat a man, almost 67 years removed from traumatic and terrifying events that shaped his life from that point forward. Now in the twilight of his life, with what struck me as a humble understanding of how important his story was to others, he was handing over the very articles of clothing that helped him make his escape. It was a humbling experience.

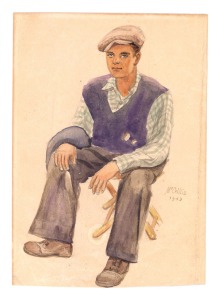

Portrait of Arthur Rohr in the clothes he evaded capture in. Painted by his tentmate John O. McCrillis.

I must admit being caught off guard by some of these thoughts. After all, I spend every day at the museum immersed in objects of similar magnitude. Yet the power of this man’s story was so inspiring. Epiphany is not a word that I use often, but I think it is quite appropriate here. The entrustment of artifacts by men like Mr. Rohr is part of why we (historians and museum professionals) do what we do. We are here because of a love of history, a passion for the preservation of that history and the understanding that stories and artifacts like Mr. Rohr’s must be safeguarded for the future. It is my hope that we do the best job possible in this endeavor and in doing so honor men like Mr. Rohr.