It’s easy for many in the United States to feel detached from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Unless you are a veteran, live near a military base, or have a relative, friend, coworker, or neighbor who served or is serving, then it’s possible that the wars have been little more than impersonal affairs on the other side of the planet that you saw or heard something about from time to time. No big deal, really.

As a nation and local communities, we owe our servicemen and women a lot. For me, those who have served in combat zones in particular are heroes who have risked their lives for their country. Their families are heroes too. I’m a veteran—I served six years on active duty in the Air Force—but I never went into combat or even deployed anywhere. Most of our men and women in uniform would rather not go into combat. But they took an oath of service and if duty meant going into combat, they went. Because we sent them.

You may have raised your eyebrows at that last sentence. I heard a story a while ago that talked about how the transition home is the new battlefield for combat veterans. One of the people interviewed talked about how important it is for the community to welcome home and reintegrate its veterans. This reintegration includes the community accepting and carrying the responsibility for the individual veteran’s war deeds. That’s a sobering thought to me. But upon reflection, it only seems right. Our Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, and Airmen are volunteers yes, but as a nation, we send them to fight our battles and so we are responsible for what they do.

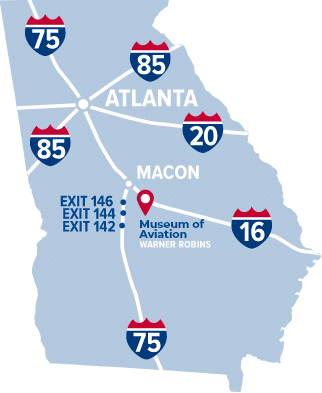

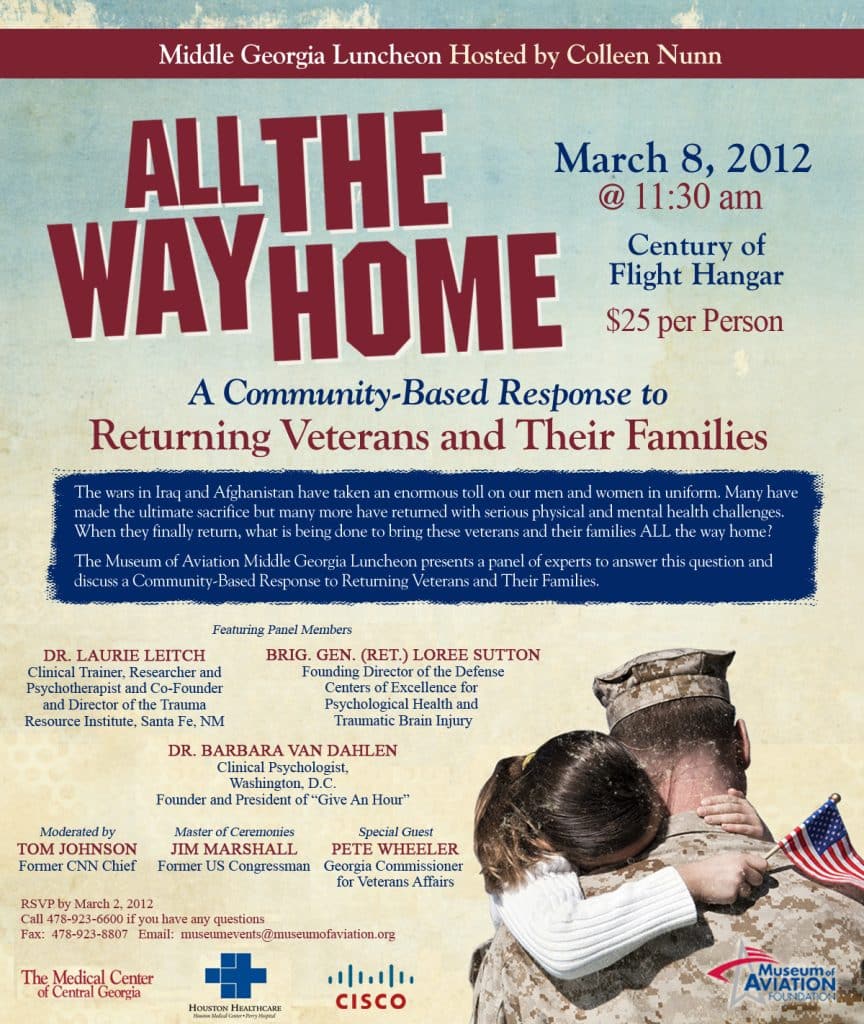

With this in mind, the Middle Georgia Luncheon on March 8, 2012 here at the museum and the topic was “All the Way Home: Community Based Response to Returning Veterans and Their Families.” The event was open to the community to learn more about our returning veterans.

My youngest brother was a U.S. Navy corpsman—an enlisted medical specialist—who deployed to Iraq three times with a Marine unit. Corpsmen are not doctors, but they’re often called “Doc” by their Marines. My brother gave me permission to share this story he wrote down some time ago. It is powerful to me because it is a real-life story that involves my own dear brother and one of his experiences in a combat zone. I’ve changed or omitted names and some details out of respect for the privacy of individuals. I added a few explanations in brackets.

My youngest brother was a U.S. Navy corpsman—an enlisted medical specialist—who deployed to Iraq three times with a Marine unit. Corpsmen are not doctors, but they’re often called “Doc” by their Marines. My brother gave me permission to share this story he wrote down some time ago. It is powerful to me because it is a real-life story that involves my own dear brother and one of his experiences in a combat zone. I’ve changed or omitted names and some details out of respect for the privacy of individuals. I added a few explanations in brackets.

“Doc, let’s go someone is hit!” Fully awake, I sat up, slipped my bare feet into my boots, put my SAPI [Small Arms Protective Insert; i.e. armor] plate carrier over my head then scooped up my rifle and med bag. My heart was pounding in my chest as I ran down the tight hallway. A lance corporal was waiting for me at the bottom of the stairs and started to lead me up as I came close. “Who is it and how bad?” I asked as we leveled out on the second floor and started up towards the third.

“I don’t know, they just started yelling for you.” He replied between breaths.

We came out onto the roof blinded by the bright Iraqi sun and I watched as some Marines lowered Corporal “Garcia” down to the ground. The left side of his face and head were covered with blood. I moved next to him, taking his head in my hands and gently probed the wound. Garcia’s eyes were open and he was looking at me trying to tell me that he knew where the sniper was. I nodded but continued my assessment. No brains were exposed and his skull seemed mostly intact, so I opened my med bag, grabbed a roll of Kerlix gauze and wrapped his head with the whole roll.

Marines stand watch on a rooftop in an Iraqi city. Scenes like this were common throughout the war in Iraq. USMC photo by Sgt. Jared W. Alexander.

Marines stand watch on a rooftop in an Iraqi city. Scenes like this were common throughout the war in Iraq. USMC photo by Sgt. Jared W. Alexander.

A gunnery sergeant, who had been acting as our platoon commander for the last couple of weeks since our lieutenant had been medevaced, moved close to me. “You done Doc? The helo is going to be on deck in a minute.”

I nodded as we loaded Garcia onto a stretcher and I watched as four Marines each grabbed a corner handle and started down the stairs. I zipped shut my med bag and followed close behind as we made our way down to the ground floor and to the rear of a hi-back HMMWV [High Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicle]. I climbed in the back and squatted next to Garcia, trying my best to keep him from being jostled as we quickly drove the quarter mile to the MSR [Main Supply Route] which was the closest paved road.

I could hear that the helicopter was close and when it came into view saw it was one of the Huey gunships and not an Army Blackhawk that we had for medevacs. I was beside Garcia’s stretcher as the helicopter landed near the smoke grenade in the middle of the road and closed my eyes as the powerful rotors blasted hot air, sand, and dust all around us.

A Marine UH-1N Huey, similar to the one mentioned in the story. USMC photo by Lance Cpl. Scott L. Eberle.

The crewman manning the minigun hopped out and gestured us toward him, so we picked up Garcia and jogged over to the open door, sliding him in. The gunner climbed in, pointed at me and yelled “Corpsman?”

I nodded and he waved for me to get in. I managed a glance at the quickly receding ground and wished for some ear plugs then turned my attention back to Garcia.

The sniper’s bullet had hit his head just behind his left temple, slipped under the scalp and traveled along his skull where it exited near the back of his head. His eyes were focusing and he was answering my questions so I was not too worried about Traumatic Brain Injury. Garcia’s blood was dripping from the back of his head down through the mesh of his stretcher, then running across the deck and out the open door where it was blown all over the inside of the helicopter. I could feel drops of it hitting my clothes and face. I turned to grab another roll of Kerlix when I remembered that my med bag was still in the back of the HMMWV.

One of the gunners noticed my trouble and opened his IFAK [Individual First Aid Kit] pulling out the small gauze packs that I took gratefully.

I pressed one lightly to the side of his head, trying to slow the bleeding without having his skull collapse in, while with my other hand I took his pulse.

Garcia had been watching my face intently as I examined him. “Don’t lie to me Doc. How bad is it?”

I grinned down at him. “You are going to be fine,” I answered confidently.

Garcia made sure I was looking at his face. “Don’t let them call my mom. She does not speak any English and will only be confused and worried. Make sure you tell them.” He laid back and seemed to relax.

I felt the helicopter bank hard as we came down towards our landing zone. Marines were waiting to carry Garcia into the STP [Shock Trauma Platoon; a battlefield emergency room] and after helping them pull his litter out I jogged behind, following them into the surgical area and listening as the doctors assessed him. I saw a chief I knew standing near the door so I made my way over to him and passed on Garcia’s message about his mom.

“I will get a Sat [satellite] phone in his hand as soon as he comes out of surgery and the docs say that it’s okay. Don’t worry we’ll take care of him” the chief promised me.

Marines and sailors rush a patient from a helicopter into the Shock Trauma Platoon area. The scene described in the story may have looked something like this. USMC photo by Cpl. James B. Hoke.

One of the nurses came over and said, “You know you have blood all over your face?”

I started to reply when the helicopter door gunner tapped me on the shoulder. “We have to take you back.”

I shrugged and smiled at the nurse then followed the gunner back to the helicopter. I sat down in the middle of the floor and took the opportunity to tie my boots and clip my SAPI plate carrier. As we lifted off the ground I shook my head at myself and swore I would never again forget my med bag.

—

Epilogue: Last my brother heard, Garcia had a metal plate in his head but otherwise made a full recovery.

– Mike Rowland, Curator